11

I N N O V AT I O N S • V O L . V I I , N O. 2 • 2 0 1 5

development in this forbidding region and to

mitigate risks to personnel, equipment, and the

natural environment.

Finding Solid Ground

One of the first difficulties to conquer relates to the

construction of essential infrastructure.

For onshore projects, for example, the frozen

layer of soil that sits about two meters down (also

known as “permafrost”) has been considered suitable

for the construction of oil and gas infrastructure. But

with the permafrost thawing, it might be harder than

expected to find solid ground for new infrastructure.

“Building on permafrost that is in a thawing

cycle is a complex challenge,” Lim says. “There is no

reliable long-term solution for that, yet.”

Construction can also be done on the soft,

slightly thawed soil that sits above the permafrost.

However, this option is even more costly because it

requires piles to be driven down more deeply to solid

ground beneath.

Given the complexity of onshore drilling in

the Arctic, it may seem somewhat reassuring that

the majority of the region’s oil and gas – about 84

percent of it – is accessible via offshore drilling. But

offshore drilling is not without its own unique

challenges. One of the biggest challenges? Price.

Burying pipelines in the seabed is extremely

expensive. And because shifting icebergs can cause

gouges in the seabed soil, pipelines need to be

buried down to 10 meters deep, a distance that

requires innovative technologies to achieve. Another

challenge is day-to-day operations: Once in place,

buried pipelines need to be inspected, monitored,

and repaired like any other lines.

Can these difficulties be whittled down to size?

Lim thinks so.

“Being able to create new technologies to

overcome Arctic limitations, while promoting

environmental stewardship, can be cost-prohibitive,”

says Lim. “So prospective companies that cannot

afford deep development spending will have to join

efforts in Joint Industry Projects.”

Protecting the Arctic,

Defining the Future

External inspection and monitoring of these deeply

buried lines are impossible using current technologies.

And traditional support vessels, with diver-based or

remotely operated equipment, are unable to access

potential repair sites when the sea is ice-covered – nine

months of the year. So the only way to stop loss

of containment, and the

consequent environmental

impact, is to completely shut

down the operation during

this period, which is rarely

desirable from a business

standpoint.

“Before we ever get to

the Arctic, the industry

will need to find a solution

to temporarily stem a leak

until the sea is ice-free,”

Lim says. Repair vessels

and equipment could then

be deployed to carry out

a permanent repair by cut

and spool replacement.

Developing such a

comprehensive and failsafe

approach to leak detection,

assessment, and repair will require a great degree of

expertise and cross-industry collaboration.

Thanks to ongoing investments in such

sophisticated technology and shared interests

among E&P companies and service providers, many

potentially catastrophic risks – for the environment

and for investors – can be eliminated. And although

some Arctic opportunities are still out of reach, it’s

only a matter of time before technology catches up.

As Lim points out, the Arctic is the last pristine

surface frontier. We all carry responsibility to maintain

that for future generations. And new pipeline

technologies will play no small part in helping to

strike the right balance between development and

preservation that will define the future of the Arctic.

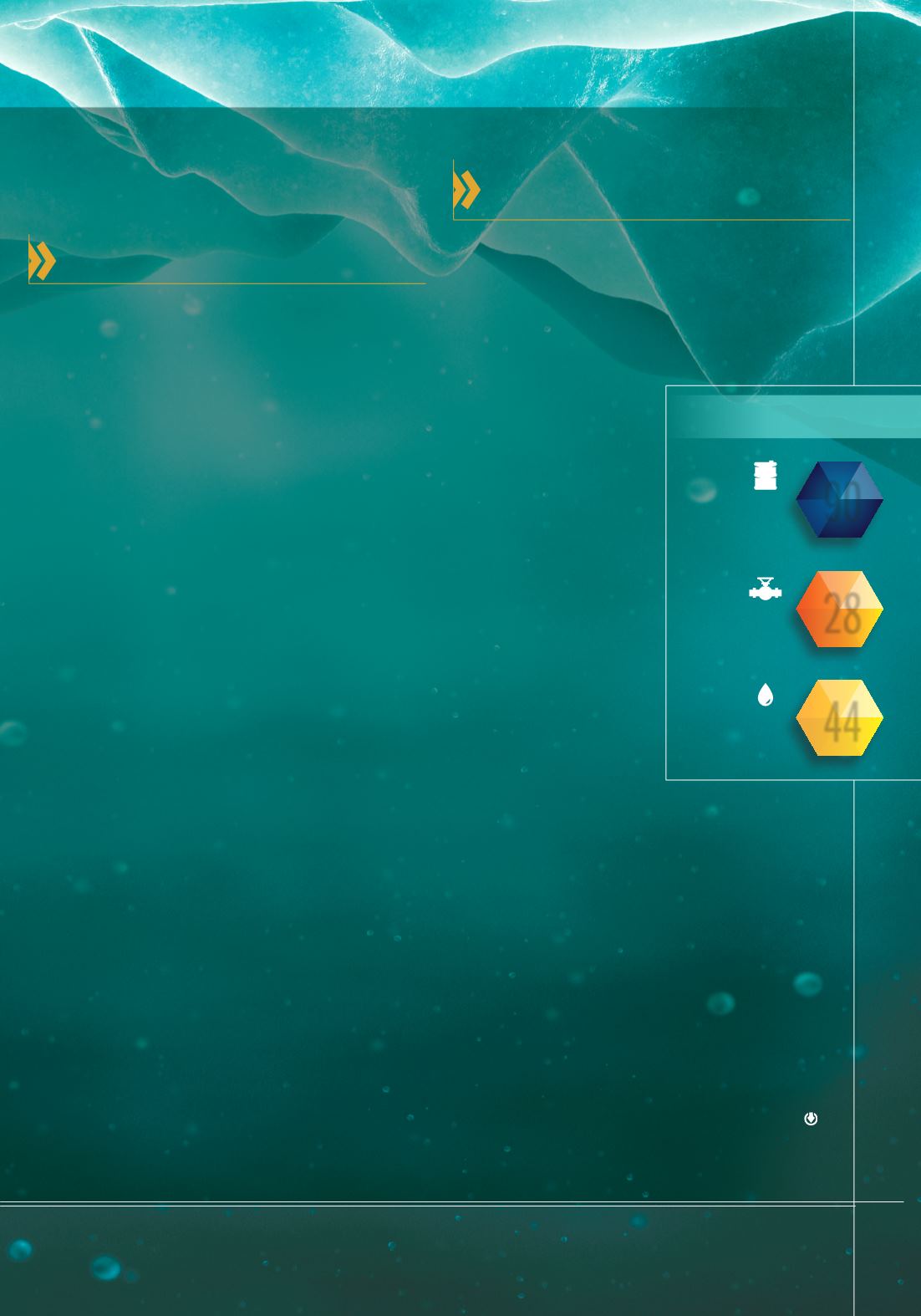

44

28

90 BILLION bbl

Oil

According to the U.S. Geological

Survey, the Arctic may hold:

28 TRILLION m

3

Natural Gas

44 BILLION bbl

Natural Gas Liquids

90