I N N O V AT I O N S • V O L . V I I , N O. 1 • 2 0 1 5

11

awareness about the importance of CCS.

Businesses and government leaders around the

world are looking to this process as a way to

prevent large amounts of harmful CO2 from

escaping into the atmosphere.

The good news is that the technology behind

CCS is nowhere near as far-fetched as the CO2

charged sparkling water in the EV-EON prank. In

fact, thanks to decades of research and development,

CCS technology is a viable option for companies

in the power, oil and gas, chemical, and refining

sectors to offset their CO2 production.

“CCS has made significant progress over the

years,” says Luke Warren, Chief Executive of

the London-based Carbon Capture and Storage

Association (CCSA). “The processes involved

are considered safe, with limited scientific and

engineering challenges.”

And it’s a solution that couldn’t have come at a

better time. In April 2014, the Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says global CO2

emissions must be cut 50 to 80 percent to avoid

the most damaging effects of climate change. It’s a

lofty goal – but it’s one that Warren and other CCS

experts think is attainable.

“CCS can achieve large emission reductions and

is considered a key option within the portfolio

of technologies needed to tackle climate

change,” Warren says. “According to the

International Energy Agency, to achieve a 50

percent cut in global emissions by 2050, CCS

will need to contribute nearly 20 percent of

CO2 reductions. Indeed, the IPCC concluded

that the cost of tackling climate change could

more than double if CCS isn’t deployed.”

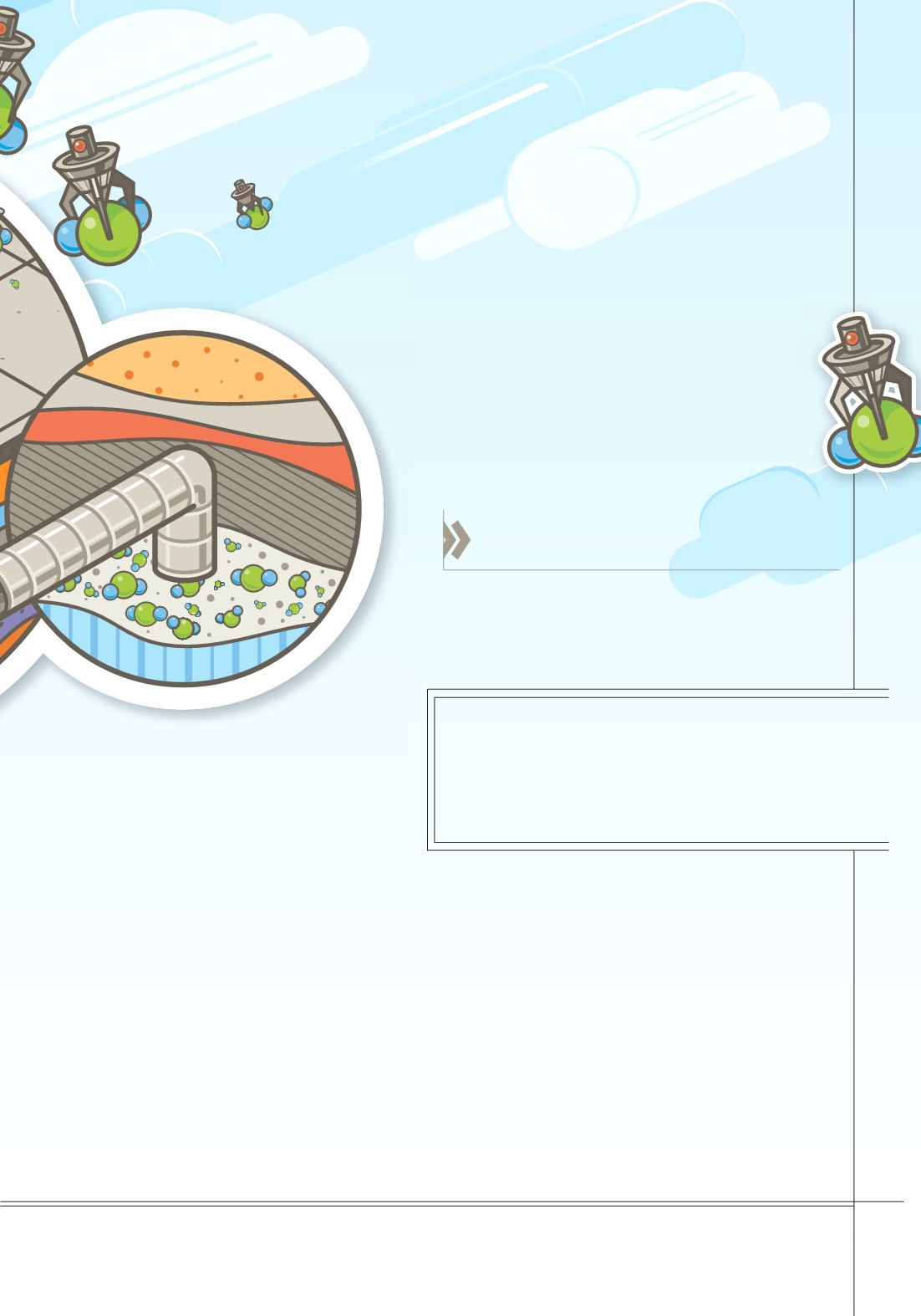

Proven Three-Step

Technology

After CCS captures CO2 emissions during industry

operations, the CO2 must then be compressed,

transported, and injected into an underground

geological formation.

One of several effective technologies for capturing

the CO2 is amine scrubbing. The process utilizes a

water solution containing organic compounds that

bind with CO2 and separate it from other emitted

gasses. The pure CO2 is then compressed into a

supercritical fluid for pipeline transfer.

Of course, once the CO2 is captured and

compressed, it has to be stored somewhere. This

step calls for injecting the CO2 “through a well into

sedimentary rocks a mile or more below the surface,”

says Susan Hovorka, Senior Research Scientist with

the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University

of Texas at Austin, which recently hosted an

CONTINUED ON PAGE 27

The processes involved are

considered safe, with limited

scientific and engineering challenges.